The most embarrassing development data cock-up of the last decade was quietly laid to rest in the back pages of The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013, published on Tuesday by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

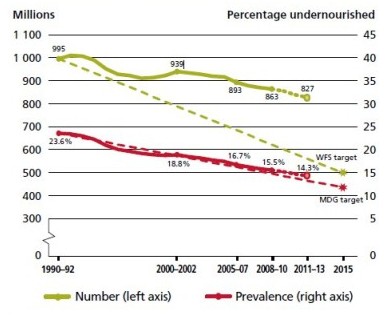

Spooked by the exponential rise in food commodity prices in 2007/08, the FAO declared in 2009 that 80 million people would be added to the 925 million already unable to access sufficient food. Writers on development issues, myself included, couldn’t resist generous use of the “billion” word, now that the count of global hunger was reputedly in that vicinity.

In 2011 the FAO took a sabbatical from publishing its annual headline statistic, such was the absence of verifying evidence for its food crisis figures. Sure enough, in last week’s report, the charted trend for global hunger shows not even the slightest blip in its steady downward path over those notorious years of food price volatility. The FAO’s text shrinks from conducting a post mortem on this debacle. In a section entitled: “What was the impact of price volatility observed over recent years?” we learn that:

The FAO’s text shrinks from conducting a post mortem on this debacle. In a section entitled: “What was the impact of price volatility observed over recent years?” we learn that:

recent data on global and regional food consumer price indices suggest that price hikes in primary food markets had a limited effect on consumer prices

Such a conclusion is too broad, typical of the oblique discussion in the report. Many of the world’s poorest households did experience real hardship from rising prices, to the extent that there were food riots in many countries.

However, in the spirit of an evident desire to move on, the important question now is whether future global hunger statistics will be more reliable if price volatility returns to haunt us.

The FAO would doubtless point to its improved understanding of the economics of price transmission. But there’s no substitute for hard data, in particular the challenge of overcoming the inordinate delay in gathering household data in the world’s poorest countries.

In Dignity For All, the UN Secretary-General’s report on the post-2015 agenda debated at the General Assembly last month, he refers to the “opportunity for a data revolution” driven by the forces of new technology. Positive stories of collating real-time data on living standards are emerging across Africa, invariably enabled by mobile phone technology.

There’s an immediate test for this embryonic revolution. Is Africa the continent driving global economic growth, as conventional GDP figures suggest? Or do these growth figures merely chart the booming demand for natural resources, the GDP froth incapable of penetrating chronic poverty?

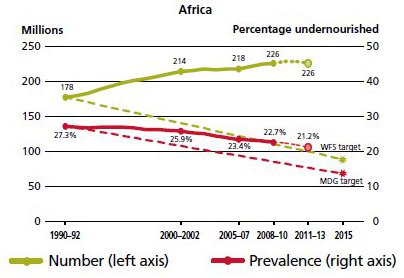

Figures published in The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013 question this “Africa Rising” narrative. With hunger falling everywhere else, the numbers in Africa continue to edge upwards: Also published last week was the Afrobarometer, a survey compiled from over 50,000 household interviews across 34 countries. It concludes: “we find little evidence for systematic reduction of lived poverty despite average GDP growth rates of 4.8% per year.”

Also published last week was the Afrobarometer, a survey compiled from over 50,000 household interviews across 34 countries. It concludes: “we find little evidence for systematic reduction of lived poverty despite average GDP growth rates of 4.8% per year.”

The relationship between GDP growth and poverty reduction is too important to wait five years for the machinery of household data collection to grind out an answer. Prizes await the organization that can successfully combine technology with the traditional skills of development intervention to solve this nagging riddle of development economics.

******

all charts are sourced from The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013

So how many of the world’s people are hungry – From Poverty to Power

Food Security Tread Softly briefings