Should nature’s assets bend to the will of markets or should the era of free market economics be consigned to history, deservedly sharing the fate of all those species whose extinction it has brought about?

This debate has frozen like a rabbit in the headlights, a failure we cannot afford as the planet lurches towards its boundaries of stability.

One symbol of the impasse is the accident-prone European Emissions Trading System, desperately sustained in intensive care by those who see no answer to climate finance without it.

Meanwhile, an alliance of more than 100 influential NGOs has called for the abolition of the ETS, depicting it as a trojan horse for future market trading in biodiversity, water, soils and forests. “Nature is not for sale” has long been the slogan of Friends of the Earth and others.

“I think that’s ridiculous,” said Professor Joshua Farley of the University of Vermont in an Oxford lecture last week, referring to those who say the concept of ecosystem services is “synonymous with commodification and integrating things into the market.”

This was a baffling remark, as Farley is known to be critical of the role of market mechanisms in the protection of planetary boundaries. A strong voice on the topic of ecological economics, Professor Farley was speaking on The Political Economy of Ecosystem Services as part of the Astor Visiting Lectureship at Oxford’s School of Geography and the Environment.

True to form, the lecture demolished the notion that awarding monetary values to systems critical to the support of human life – such as the ozone layer, a stable climate and water purification – might rein in our unsustainable consumer culture.

In further apparent sympathy to critics of the “financialisation” of nature, Farley drew attention to the failure of markets to protect basic human needs. He repeatedly observed how the doubling of world food prices in 2007 passed virtually unnoticed in the richer economies, whilst driving millions below the hunger threshold in countries where families commit high percentages of their income to food.

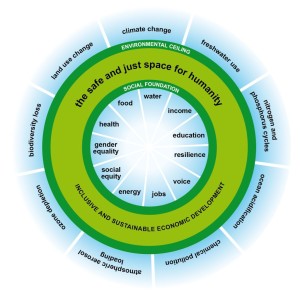

Given the Oxford location of the lecture, Joshua Farley may have missed a trick in not relating his vision of protecting both planetary boundaries and basic human needs to “the safe and just space for humanity,” a particularly helpful concept for sustainable development created by Kate Raworth of Oxfam.

Professor Farley offers a much-needed economic template to flesh out the conceptual strength of Oxfam’s idea. Familiar market-based economics cannot be entrusted with the task of protecting natural boundaries or human needs. Instead we must look to science to establish how much we can safely consume and to the principle of justice to award individuals an equal share.

Only when those boundaries are secure can we allow the forces of market economics free rein. “We cannot integrate ecosystem services into the market model, but rather should adapt economic institutions to the characteristics of ecosystem services,” was Farley’s conclusion.

This was the nuance that might explain Farley’s rather ambiguous position in the political debate. As he explained early in the lecture:

A lot of critics say: “look – this is the commodification of nature; this is like the neoliberal model extended to nature. It’s totally inappropriate and therefore we should totally abandon the idea of ecosystem services.”

What I actually want to do in this presentation is to say that’s a totally false dichotomy…my own view is we can’t fit ecosystem services in the market model so it would be a foolish quest and, even if we could, it would lead to undesirable results. But in order to come to those conclusions we really need to understand what ecosystems are and how they function ….in order to decide what economic institutions are appropriate for allocating them.

Farley didn’t enlarge on how these institutions might become politically feasible. To that extent the lecture became a microcosm of the curse of green economics – that broadly like-minded constituencies have generated wonderfully stimulating ideas without locating a political roadmap or uniting around sufficient common ground to spur change.

Even on the extremes of left or right, rich or poor, there are few who would deny that our contemporary pursuit of GDP growth is dysfunctional in neglecting nature in its system of economic value.

Farley’s mechanism for ecological economics is to diminish the role of conventional money in our system, supplementing it with personal environmental allowances.

At a time when both US and UK economies are addressing their problems by printing money, it’s no wonder that his political vision remains under the radar.

******

Synopsis of ODID and ECI Visiting Lectureship Professor Joshua Farley

The Political Economy of Ecosystem Services – podcast of lecture, from Environmental Change Institute

Scrap the EU ETS – press release

⇒ more posts about the economics of ecosystems and biodiversity