Not so long ago there were 57 licensed premises within 30 minutes’ brisk walk of my home in the centre of Winchester. For years I wondered how I made my choice, typically without much hesitation, as I headed out for routine refreshment.

It wasn’t simply the quality of fare or service, as the improvement of these establishments over the last 20-30 years had levelled up such criteria. Eventually, staring at walls, as one does over a drink at the end of a long day, the truth dawned.

I was staring at a sporting image, not the wall, intrigued for the umpteenth time about questions it raised that I could never quite answer. It had not occurred to me that picture-hanging decisions by pub management could be so profound. Yet there was no doubt that a mild hypnosis existed in four separate establishments, setting my direction of travel for many of those evenings.

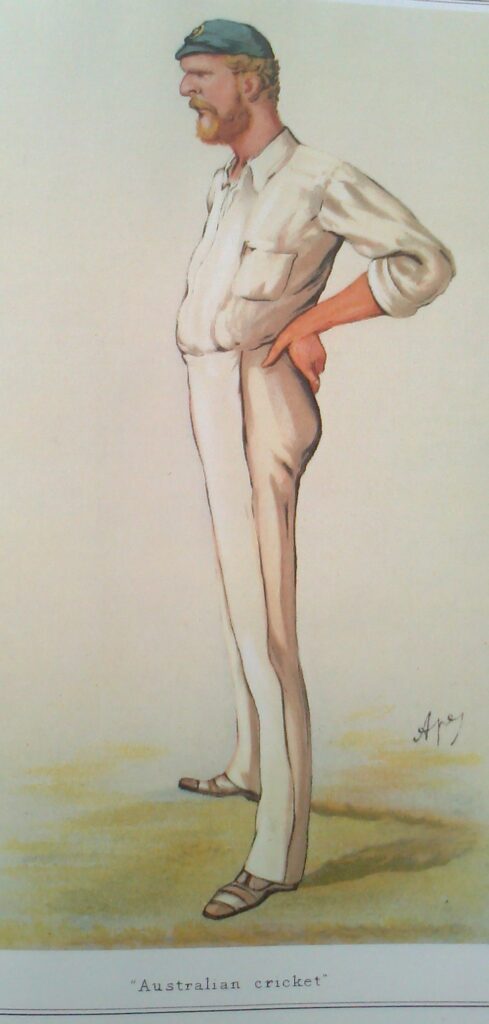

I was drawn to Bonnor, the Australian cricketer, not for the intrinsic merit in the print, but because he was there. The 19th century caricatures of Vanity Fair are ubiquitous in Winchester, as elsewhere, the judges, politicians, and celebrity aristocrats parading the confidence of upper class Victorian London.

It took 9 years for Vanity Fair to feature a cricketer, inevitably W.G.Grace, already recognised as the champion in 1877. He was quickly followed by Spofforth, the greatest Australian cricketer, and then Lord Harris in 1881, a natural fit for the Vanity Fair set.

George Bonnor was next in 1884. He rarely turned the tide of Ashes test matches in which he played between 1880 and 1888. He was an outback sheep farmer who loved everything about the outdoors. He had no natural place in a London society journal.

But Bonnor had hit a ball over the Oval pavilion. He could throw a cricket ball 120 yards at will. Standing at 6 feet 6 inches, he towered over his contemporaries. His exploits contributed to the lore of Ashes cricket that was to become a national obsession before the turn of that century.

******

The teapot attitude presented by the Vanity Fair artist belies Bonnor’s reputation as a gentle giant. He never married and I like to think that he would have enjoyed the company of the unidentified sporting Edwardian lady in the superb photograph in a pub that rather stretched my 30-minute rule.

Her confidence in handling the shotgun is absolute. The choreography of the photograph is highly professional. Would a husband have knowingly commissioned such an image? Who was she? There’s a story here and I’ve never found it, nor seen a copy of the photograph elsewhere.

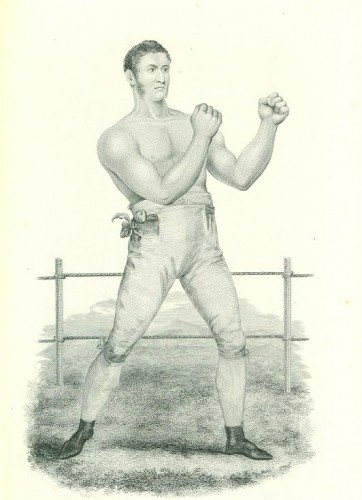

There were no gentle giants in the sport of John (“Jack”) Langan, the Irish champion prize fighter whose framed torso was on guard close to the door of the bar, possibly not the ideal inspiration for late evening customers decanting on to the streets of Winchester.

The year of Langan’s greatest exploits, 1824, lies within my favourite period of English sporting history. The public had acquired its uniquely English obsession for cricket, racing, boxing and fives, yet detailed histories of these sports are tantalisingly difficult to piece together. Rules were inconsistent, travel difficult and venue organisers constantly wary of upsetting authority, such was the association of all sports with unregulated betting. Crowd violence and the risk of serious injury to the participants were added deterrents for prize fights.

Needless to say, any single round of a bare-knuckle fight would today activate concussion assessments, ending proceedings for both contestants. Langan went over 70 rounds in each of his two epic defeats by the English champion, Tom Spring, in that year. Neither man ever fought again. The second contest was held in Chichester, just possibly accounting for a print turning up in Winchester.

******

The last of these visual pub diversions is the strangest. It had no right to hold my gaze yet invariably created anticipation on crossing the threshold, especially in the summer months. The picture lacked any hint of identification – untitled, unsigned, undated. It offered a simple image of a batsman ready to face, in immaculate white flannels and traditional cap, surrounded by a plain green background. There were no stumps, creases, or wicket-keeper.

I imagined it might have started life as a 1950s book cover for boys’ fiction, with cricket offering excitement and moral direction. It was the stance that fascinated me; the classic position, bat down, head up looking straight out of the frame, this batsman was perfectly set, with a stillness that I never achieved in decades of striving. How did the artist capture this Gower-like quality in such a modest commission?

******

Covid intervened, imposing a long period of abstinence from my simple pleasures. It also put the hospitality industry on the rack, first fearing for its survival, then frantic to read the runes of post-Covid leisure. There have been closures, new “concepts”, and obsessive refurbishment.

I looked forward to returning to the old ways. My automatic pilot initially steered me to familiar venues but something was wrong. I fidgeted and left unsatisfied.

My favourite places had succumbed to the old adage that, as times change, you must change your pictures. In this desperate act of cancellation, every one of my hypnotic sporting prints, in their separate establishments at each point of the Winchester compass, has vanished.

A final curious twist; the wall that hosted that 1950s batsman has been left clear, papered with a rich green fabric which I’m convinced is identical to that of his background field.

******

Winchester’s most famous pub, The Wykeham Arms, has never changed its pictures in nearly four decades of my acquaintance. Multiple images of Nelson and his flagship lurch untended at angles more suited to their voyages than this place of fine dining.

Periodically I grumble to the staff that the decor compels a total makeover. I loathe the vintage school desks, their gaping inkwells stirring memories best forgotten.

Never, they say. Never change what draws people in, even if they don’t realise it.

******